Creating Local Community in a Global World

Written by Anu M. MitraPhilosophers from the ancients to John Dewey and Dr. Seuss have debated the meaning of community. What is it? How is it fostered? Who belongs to a community? Who, by virtue of their beliefs or practices, are excluded from it? In her book, Education and Community, (2006), Diane Gereluk explains that the word community is derived from the Latin word “communis,” which evokes the dual concepts of “with obligation and together” (p. 7). This is to say that being in a community is a shared experience with both benefits and expectations. Peter Block, expanding on this idea in Community: the Structure of Belonging, (2008), writes: “Community…is about the experience of belonging.” He goes on to say that belonging can at once mean “being related to” and “being an owner.”

Seattle Artist’s Magic, artwork by Taylor Hammes

Both meanings are ripe with possibilities because the sense of belonging can allow oneself to feel at home in the world, no matter where one is. This togetherness can provide a sure antidote to the epidemic of loneliness tearing through America in our present moment. Block also writes,

“To belong to a community is to act as a creator and co-owner of that community.” Our work becomes “fostering among all of a community’s citizens a sense of ownership and accountability” (p. xii). How we grow within us a “sense of ownership and accountability” becomes key to how society evolves and democracy strengthened.

It is no surprise then that finding a void in the system, the 21st museum stepped in and is taking a crack at defining community. It’s going a step further by beta-testing it and creating conversation on what it means to belong. Even prior to serving in this activist role, the museum has historically served as an important provider of knowledge, being as if it were a supplement to formal education. The critical thinking benchmarks that are specific to each stage of formal education are often closely tagged in the learning and education departments of museums. What schools and colleges routinely learn in the classroom becomes firmly cemented in museum offerings to the public.

Image by Hosptiality House

It follows naturally that with exposure to education, the scope of our learning changes. As we become exposed to art, our views of the world pan out in a wide-angle focus. We see opposing points of view with greater clarity. We learn about difference and how it has been addressed historically. We become, overall, more aware community members. After all, art that is relevant to one’s experience is the kind that draws us inward into a reflection of larger ideas.

The American critical scholar Bell Hooks focuses on this practice in her landmark book, Art on My Mind (1991). In its pages, she promotes the idea of “oppositional looking”—a way of seeing the world through art that is more expansive than any physical landscape. She writes,

“rather than view art objectively, the spectator can place herself in a position of agency through a more embodied subjective viewing process that takes into account questions of difference, sexuality and power” (p. 3). Simply stated, we put ourselves in the shoes of another, with our mind, heart and soul, and we try and experience for a moment what it feels to be the other.

Illustration by Celia Jacobs

At the Cincinnati Art Museum, for example, community is intentionally developed in home-grown ways, beginning with the geographic area of Walnut Hills that immediately borders the Museum. In 2022, approx. 7,000 community members were served through approximately 120 programs, all reflecting a carefully choreographed DEAI Strategic Plan that intersects all segments of life. A Global Music and Wellness program provides outreach to refugee populations. Science and art are comingled in a program with COSI—the Columbus Center of Science and Industry. Other partnerships include ones with ROMAC—the Robert O’Neal Multicultural Arts Center and WordPlay Cincinnati, among others. “Through the power of art we contribute to a more vibrant Cincinnati by inspiring its people and connecting our communities” reads its mission statement and from the packed galleries, one can tell that the point is hitting home.

Image by bold business

At the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati, teens are encouraged to attend Art Prom—where they make friends, make art and dance their “faces off.” Families go hiking with the Cincinnati Park Foundation while they stop to observe and sketch. People of all ages take part in a Creative Writing experiment. And individuals with sensory issues find their niche on Sensory Friendly Mornings. The point of this abundance of activities is to create more welcoming, less intimidating spaces in which people can be themselves.

Nationwide, museums are taking more of a listening stance. Paying attention to the visitor. Heeding their needs. Reflecting in the art the visitor’s experiences. This is community building at its most intimate, one person at a time, each person being seen and acknowledged for who they are. It is meeting people where they are and choosing to talk about art in everyday speak. This is hard, hard work but it must be done in the name of true belonging.

Myriad communities

Horace Pippin, Christmas Morning, Breakfast, 1945, oil on canvas, 21 1/8 x 26 3/16 in.

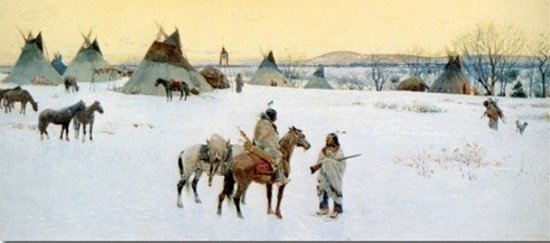

Henry Farny, Return from the Hunt, 1894, gouache and watercolor over pencil, 7 1/4 x 16 1/8 in. (18.4 x 41 cm)

Grant Wood, Daughters of Revolution, 1932, oil on masonite, 20 x 39 15/16 in. (50.8 x 101.4 cm)

Joseph Henry Sharp (1859-1953), United States, Fountain Square Pantomime, 1892, oil on canvas.